Lessons from Our Past: Cooperative Extension Services and Citizenship Schools

The Agricultural Challenge

This isn’t the first time we’ve faced the daunting task of training millions of adults to master a complex technological skill. In the late 19th and early 20th century, the US faced a similar challenge to the one posed by Emerging Tech today.

A modern society can’t function unless farmers are productive enough so they can feed the vast majority of people who no longer work the land. To pull off this agricultural revolution, millions of farmers had to master new skills and knowledge – the key elements of soil science, plant science, entomology, and a wide range of other information and practices that made up modern farming practices.

From a distance, teaching farmers about modern farming practices might seem much easier than teaching programming to people who’ve never written a line of code. But the gap between what most farmers did and modern agricultural was so large and difficult to bridge that it took more than 50 years of large-scale experiments to figure out how to do it.

For example, after many years of volunteer-driven efforts to spread modern practices, in 1862 Congress and the Senate reluctantly concluded that a more dramatic government intervention was needed. The Morrill Act created a system of land-grant colleges to teach agriculture and other practical arts. The Act was driven in part by the belief that the practice of modern agriculture was so complex that only by helping many people gain a college degree in it could the US transform the world of farming. But these and other efforts failed to train enough farmers to substantially change farming practices.

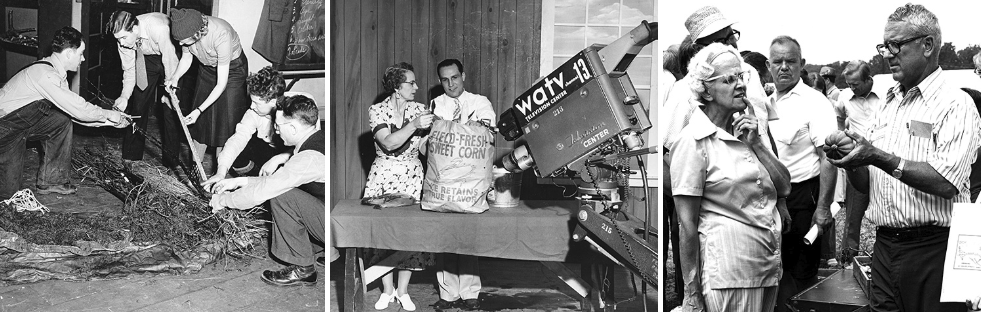

Finally, in 1914, the US came up with a strategy that worked. Drawing on the lessons learned from years of experimentation by individual states, the Smith Lever Act created a community-oriented approach called Cooperative Extension Services.

Extension Services

Extension Services were successful because they created a rich web of support to help farmers make the transformation to modern farming. In doing so, they employed 4 strategies:

- Focus on Communities, Not Just Individuals. Most of today’s efforts at democratizing tech are focused on individuals. And although this approach has some advantages, it often ends up masking the fact that these efforts are creating opportunities in some communities but not others. Extension Services used a community-oriented approach, which asked whether communities, not just individuals, were succeeding in adopting modern agricultural practices.

- Harness the Power of Community. Because Extension agents were deeply embedded in communities, Extension Services was able to leverage a community’s assets, including the bonds of friendship and support among farmers, to have a far greater impact than they otherwise could have. Without drawing on each community’s strengths, it’s doubtful that Extension Services could have succeeded.

- Move the Tech Closer to the People. Extension Services agents not only helped translate complex scientific concepts so they were accessible to ordinary farmers, they also helped create a feedback loop that ensured that the tools and practices proposed by researchers were modified so they fit farmers’ needs and incorporated their experiences.

- Operate at Scale. Extension Services operated in every agricultural community across the US. Every county had one or more extension agents who fostered this rich web of support, most of whom were backed up by faculty and staff from their state’s Land Grant colleges. And in a significant number of states, the scope of Extension Services’ operation was remarkable. In New York State, for example, by 1948 Extension Services had built a network of 32,000 trained volunteer local leaders and committee members, who were supported by 383 agricultural and home economics staff affiliated with state colleges and universities.

The Limitations of Extension Services

But Cooperative Extension Services also has a more complicated lesson to teach us. Extension Services has demonstrated that it’s a remarkably effective way to serve a specific audience. However, at different times and in different places in the US (and around the globe), it has often been designed to help some audiences while inflicting terrible harm on others. For example:

- Throughout much of its history it actively discriminated against African-American farmers and ignored the needs of immigrant farm labor

- Over time, as it began to embrace the ethos of “get big or get out,” it increasingly focused on the needs of Big Ag to the detriment of the small farmers it was originally designed to serve

At the same time, the most bottom-up, grassroots-oriented traditions of Extension Services have become so important to today’s efforts to reduce global poverty that in 2015, Bill and Melinda Gates argued that

investing in extension so that it helps more farmers in more places—women as well as men, smallholders as well as more commercial farmers—is the only way to reap the full benefit of innovation.

How do we embrace the best parts of Extension Services’ traditions and avoid the worst? By learning the lessons of another remarkable educational effort: the 1960s Civil Rights Movement’s Citizenship Schools.

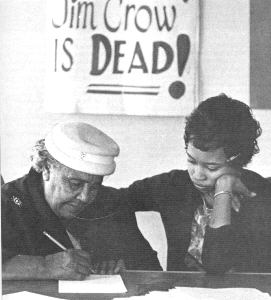

Citizenship Schools

One of the major challenges facing the 1960s Civil Rights Movement was how to overcome voter suppression laws designed to stop African-Americans from voting by requiring that voters must be literate. How could the movement help African-Americans throughout the rural, agriculturally-dominated South to learn to read and write in a relatively short period of time so they could build political power? The solution: Citizenship Schools.

As we will see in our discussion of Strategy #3, Citizenship Schools played a vital role in the success of the Civil Rights Movement. Like Extension Services, Citizenship Schools were designed so they were deeply rooted in their communities – a critical step if they were going to help people overcome their feelings of shame about being illiterate and their fears of violent retaliation. And like Extension Services, they operated at scale: a total of 1,000 Citizenship Schools were set up throughout the Deep South.

Where Citizenship Schools differed from Extension Services is that Citizenship Schools were deeply rooted in civic literacy and activism. While some traditions of Extension Services were grounded in civic engagement, Citizenship Schools were designed from the ground up to help their students learn how to fight for their freedom and for their community. In addition to teaching basic literacy, Citizenship Schools taught their students the civic skills necessary to win the struggle for voting rights, save document go to sleep as well as to understand the nuts and bolts of how the political system worked so students could use political campaigns and community organizing to make their voices count.

When the Internet first took off, it was sold as a tool for empowering everyone; instead, it became one critical foundation of an economy where communities from Harlem to Harlan County were left behind. If we don’t want to repeat that mistake, we must ensure that every community has a seat at the table – and to do that, we’ll need to draw on the lessons of Citizenship Schools. Only by ensuring that there are enough people in every community who understand both how to code and how to fight for their community’s future can we be confident that emerging tech opportunities will be accessible in every community and that every community will have a real say in who benefits from this new economy.

Letting Go of Fear

Ultimately, the most important lesson we can learn from Extension Services and Citizenship Schools is that we can’t be afraid to think big.

We have a rare opportunity to make more emerging tech jobs more accessible today and to create a better future for all tomorrow. But to seize it, we need to think boldly, dream, and then act on a large enough scale to realize those dreams.

Next: Caveats and Scope

Last: Is Truly Democratizing Emerging Tech a Pipedream?

Up: Introduction