What Citizenship Schools Can Teach Us

In the 1950s and early 60s, one of the major challenges the Civil Rights Movement faced in the Deep South was that voter suppression laws barred anyone from voting unless they could read and write. How could the movement help enough African-Americans become literate quickly enough to build political power – especially in an environment where any efforts by African-Americans to win the right to vote might be violently suppressed? The solution: Citizenship Schools.

Citizenship Schools had a deep and profound impact on the Civil Rights Movement, which is why Dr Martin Luther King Jr called their creator, Septima Clark, the “mother of the Movement.” Citizenship Schools taught their students the basic literacy needed to overcome voting restrictions. But they also taught them the civic literacy skills needed to win the struggle for voting rights and to understand how the political system worked so they could make their voices count.

A Community-Oriented Approach

Some of the strategies Citizenship Schools used were very similar to the best traditions of Extension Services:

Harness the Power of Community

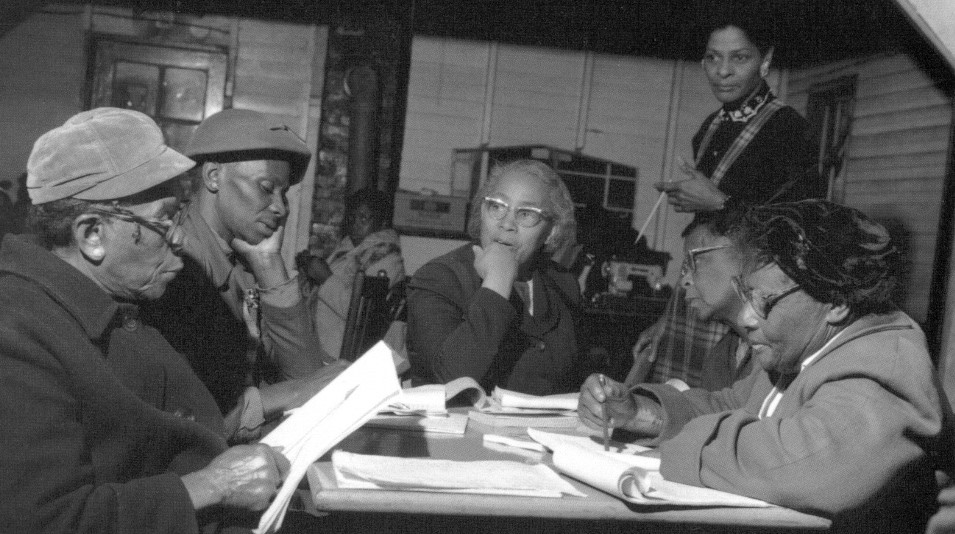

By being deeply embedded in communities, Citizenship Schools were able to leverage a community’s strengths, including the bonds of friendship and support. For example:

- When recruiting a school’s teachers, they targeted people who civil rights activist Dorothy Cotton described as “people with Ph.D. minds who never had the chance to get an education who were the natural leaders in their communities”

- Teachers often mobilized people in the community to help set up the physical space of the school, which could be located in the back room of a local store, a church, a beauty parlor, or other community institutions, which also allowed them to hide the school from local white elites

- Teachers used local social networks to recruit students, who might be leery of taking a class not only because of the fear of white reprisals but also because of the stigma of illiteracy

- When students’ training was over, teachers encouraged them to recruit their friends, neighbors, and other people from their community to take the next class

Be Responsive to Local Needs, but Operate at Scale

Citizenship Schools were grounded in helping people develop more self-sufficiency in their daily lives and gain an understanding of how they could help change their local community. At the beginning of the first class, for example, teachers would ask students what they wanted to be able to do with reading and writing – e.g., being able to read documents you had to sign – which were then incorporated into the class. Classes also often discussed local community issues and how they might be addressed.

Although Citizenship Schools were designed to incorporate the unique circumstances and needs of an individual community, to play an important role in changing the South they had to operate at scale. According to historian J. Douglas Allen-Taylor:

The Citizenship School Movement trained more than 10,000 community leaders from 1957 to 1970 through nearly 1,000 grassroots, independent schools that operated at one time or another in every county in South Carolina, nearly 90 counties in Georgia, and in all of the heavily-Black areas of the rest of the Deep South. At one point in 1964, almost 200 schools operated simultaneously. Former Atlanta Mayor Andrew Young… said that the Citizenship Schools were the “foundation” of the civil rights movement, “as much responsible for transforming the South as anything anybody did.”

Civic Training in the Service of Justice

Although some Extension Services traditions embraced more moderate forms of civic engagement, Citizenship Schools were designed from the ground up to combine technical and civic skill training in order to fundamentally transform the economy and society, helping African-Americans win their freedom in the South.

As we will discuss later in this chapter, Citizenship Schools faced a set of educational and political circumstances very different from our own. But we can still learn some useful lessons from some of the strategies they used to achieve their goals.

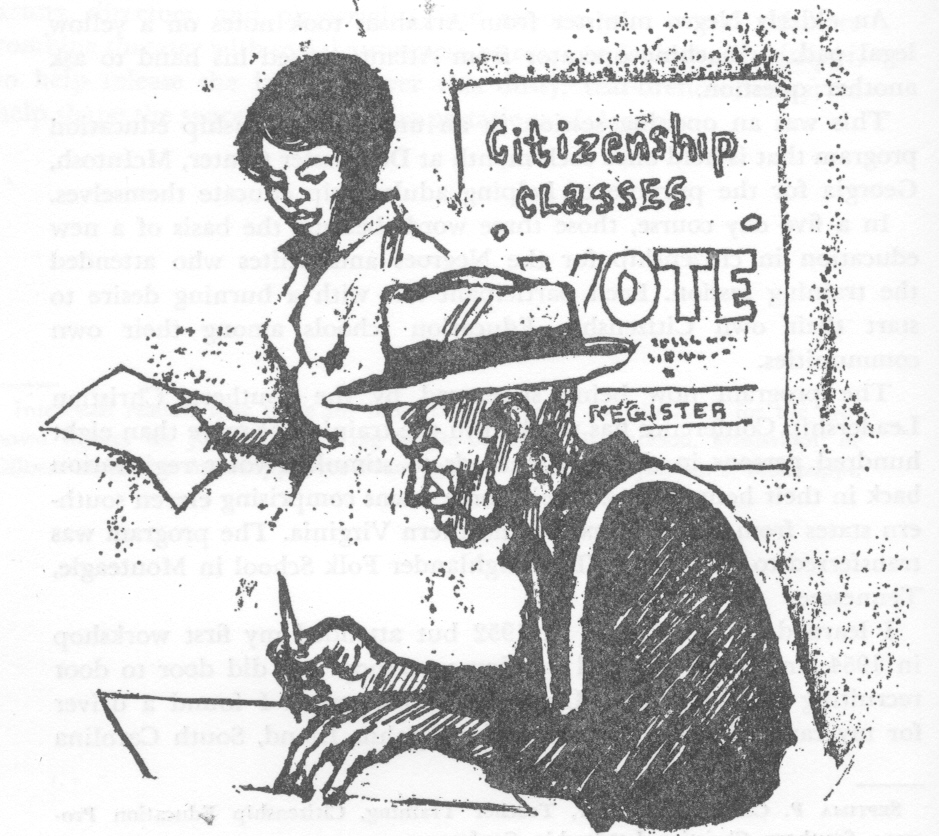

Blending Technical and Civic Training

Citizenship Schools didn’t treat basic literacy and civic literacy as two separate subjects. They intertwined teaching reading and writing with understanding how the political system worked, from understanding their rights to learning the nuts and bolts of lobbying for better local services. The curriculum was designed to develop both the skills and the confidence to use them on behalf of themselves and their community.

This intertwining of basic and civic literacy occurred in every facet of the training. For example, in the Citizenship School workbook for students in Georgia, here’s what it had to say about learning to write:

As you improve your writing, new worlds of pleasure will open and old fears will pass away. You will enjoy writing your friends. You will be able to write to your newspaper and express your views on the events of your community. You can write your Congressman or Senator to help him to vote for things that will help your people, and you will not be shy about filling out job application blanks, signing your name to your checks or registering to vote.

Similarly, students would begin by learning to read simple words in the workbook and use them to write brief stories about their lives, then read more complicated stories about the lives of African American political heroes such as Crispus Attucks – whose story included the discussion question, “how is the problem of [British] taxes like Negroes’ problem of voting?” – and Harriet Tubman. Other readings included passages on the political philosophy of nonviolence.

Learning by Doing, Developing Leaders

The workbook ended with a section on “Freedom Songs to Read and Sing.” But right before that was a section entitled, “Planning a Voter Registration Campaign,” which asked students for a substantially bigger commitment than singing:

A good citizen must be a registered voter. But the job does not stop there. We cannot rest until every citizen is a registered voter. You have been helped to register through this citizenship course. It is now your turn to help your neighbors. Plan a registration drive for your neighborhood or community:

This call to action was followed by a planning sheet, which include questions about a student’s neighborhood such as:

- “What is the size of the Negro population?”

- “How many can we get to register?”

- “Number of Volunteer Workers needed to cover area”

- “Organizations to take part in the drive”

Next came a template to “Canvas your Neighborhood” as well as a list of “Suggested Steps for a Block Party” about voter registration, which included the following:

- “Plan a meeting for next week to give help to each other (if possible, arrange to start a Citizenship School)”

- “Have someone contact the persons who did not show up at the [block party] meeting.”

There were 2 reasons for this approach. First, according to Clark:

There were 2 reasons for this approach. First, according to Clark:

The basic purpose of the citizenship schools is discovering and developing local community leaders. One of the unique practical features of the concept is the ability to adapt at once to specific situations and stay in the local picture only long enough to help in the development of local leaders. These are trained to carry on an ever growing program of community development. The secret stems from the emphasis and the reliance on local leadership. It is my belief that creative leadership is present in any community and only awaits discovery and development.

The other reason behind this approach was the belief that there is a limit to what you can learn in a classroom. Action in the real world is needed both to fully learn these lessons and to build the confidence to act.

Citizenship Schools use a similar approach for training its teachers. In addition to being required to take a 5 day workshop on how to run a Citizenship School, teachers were expected to research the hours and location of the voter registration office, election dates, the names of local politicians, and the location of the nearest Social Security office. Workshops ended with a discussion of how they would use what they learned to make a difference in their community when they got back home. Many people who became local civil rights leaders started out as being trained to run Citizenship Schools classes.

Next: Applying The Lessons of Citizenship Schools

Last: Why Training In Civic Engagement Is so Critical

Up: Combine Tech & Civic Engagement Training